The Heart of Hawaiian Culture: Taro Farming and Making Poi

Native Hawaiian culture is filled with traditions that connect people to nature, family, and community. One of the most important traditions is taro farming and poi making. Taro, or kalo in Hawaiian, is more than just a plant—it’s a cultural symbol and a sacred food. It plays a big role in history, spirituality, and everyday life in Hawaii. Let’s explore the rich tradition of taro farming and how this humble root becomes the beloved Hawaiian dish called poi.

What Is Taro?

Taro is a tropical plant that grows in wet or dry soil, but the wetland method is most common in Hawaii. The heart of the plant is its starchy, underground root, called the corm, which can be cooked and eaten. Taro leaves are also edible and used in dishes, but the root is the star ingredient for making poi.

Taro is considered sacred to Native Hawaiians and deeply connected to their beliefs. In Hawaiian mythology, taro is said to be the older brother of humans. According to the legend, the sky father Wākea and earth mother Papa had a child named Hāloa-naka, who was stillborn. From this child’s grave grew the first taro plant. Their second child, named Hāloa, became the first human ancestor. This connection makes taro a symbol of family, unity, and life.

Taro Farming: A Traditional Practice

Taro farming is an age-old practice in Hawaii that requires skill and hard work. Native Hawaiians traditionally planted taro in loʻi, or wetland taro patches. These were carefully designed fields that used water from streams or rain. Each loʻi was surrounded by ʻauwai (irrigation channels) to keep a steady flow of water, which helps the taro grow strong and healthy.

Farmers worked in harmony with nature, understanding the seasons, the water flow, and the land. Traditionally, taro farming was not just about growing food—it was a spiritual practice. Hawaiians honored the land (ʻāina) and viewed it as a living being that provided for them.

Today, many Native Hawaiian farmers continue this ancient practice, preserving their culture and teaching younger generations. They rebuild old loʻi and share knowledge about sustainable farming methods. Modern taro farming combines tradition with science to protect the land and keep taro thriving.

How Poi Is Made

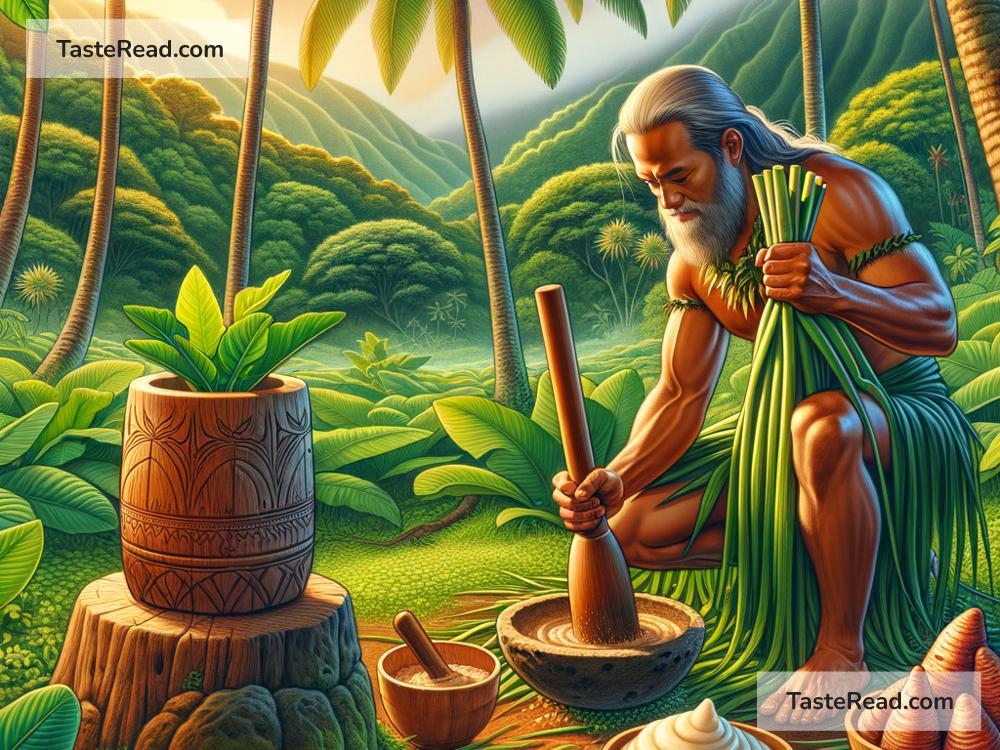

Once taro is harvested, the next step is making poi, a traditional Hawaiian food. Poi is created by steaming or boiling taro roots and mashing them into a paste. Traditionally, Hawaiians used a pohaku kuʻi ʻai (stone pestle) and a papa kuʻi ʻai (wooden board) for this process. This method required skill and strength, as the farmer worked to create a smooth, sticky paste.

After the taro is mashed, water is added to achieve the desired consistency. Some people prefer thick poi, while others like it thinner. Poi has a mild, slightly tangy flavor that comes from the natural fermentation process when it is left to sit for a day or two. Many Hawaiians enjoy poi with fish, meat, or vegetables, but it can also be eaten alone.

Poi is much more than food—it’s a connection to ancestors and tradition. Eating poi reminds Native Hawaiians of their roots and their responsibility to care for the land.

Poi as a Staple and Symbol

In Hawaiian culture, poi has always been a staple food. It was easy to store, nourishing, and suitable for people of all ages. Babies, elders, and everyone in between could eat poi for its soft texture and health benefits. It’s high in fiber, vitamins, and minerals while being easy to digest.

Poi also has a deeper meaning. At family gatherings or ceremonies, poi is often placed at the center of the table. In Hawaiian tradition, this symbolizes peace and respect. Arguments and disagreements were not allowed at the table while kalo (poi or taro) was present. The plant’s sacred origin reminded people to honor their bond as family and community.

Preserving the Tradition

Over time, taro farming and poi making faced challenges. Colonization, urban development, and imported foods led to a decline in traditional farming practices. Many loʻi were abandoned, and poi became less common. However, in recent years, Native Hawaiians have worked hard to revive these traditions.

Organizations and farmers have dedicated themselves to protecting taro farming and promoting sustainable practices. Many schools and community groups teach children about taro farming, showing them how to care for loʻi and make poi. These efforts help preserve Hawaiian culture and keep the connection to the land alive.

A Taste of Hawaii’s Soul

Taro farming and poi making are not just about food—they’re about honoring the land, the ancestors, and the traditions that hold a community together. Each bite of poi tells a story of history, hard work, and gratitude.

Whether you’re visiting Hawaii or learning about its culture from afar, understanding taro farming and poi making offers a glimpse into the heart and soul of Native Hawaiian life. It’s a tradition that reminds us of the importance of family, respect, and caring for the earth. The next time you see taro or taste poi, remember—it’s not just a dish. It’s a symbol of Hawaiian identity and an ancient connection to the land that provides for all.